Reinforcement Learning from First Principles to Robotic Control

A Reinforcement Learning Journey: From First Principles to Robotic Control

How can we teach a machine to perform a complex task, like riding a bike or mastering a game, without providing explicit instructions for every possible situation? This is the fundamental question that reinforcement learning (RL) seeks to answer. Unlike other machine learning paradigms that rely on static datasets, RL is about learning through active interaction with an environment. The agent, or decision-maker, learns by taking actions and observing the consequences, guided only by a sparse signal we call "reward." Its goal is to develop a strategy, or "policy," that maximizes its cumulative reward over time.

This learning process presents a unique and difficult challenge: the trade-off between exploration and exploitation. The agent must exploit what it already knows to gain rewards, but it must also explore new, untried actions to discover potentially better strategies. Furthermore, the consequences of an action might not be apparent until many steps later, a problem known as credit assignment.

This article documents my self-directed study of this field, structured as a series of key learnings from foundational papers and algorithms. My journey revealed a clear progression of ideas:

- It began with formalizing the problem using the language of mathematics to define states, actions, and rewards.

- It then moved to the core of modern RL: direct policy optimization, and the series of innovations required to make it stable, from baselines to trust regions.

- This theoretical foundation enabled an understanding of state-of-the-art practical algorithms like PPO and TD3, which solve critical issues like instability and overestimation.

- Finally, applying these algorithms to robotics forced a shift in perspective from pure algorithms to holistic systems thinking, where the real-world challenges of engineering and integration come to the forefront.

What follows is a technical narrative of that journey, from first principles to the complex systems required for robotic control.

Phase 1: Formalizing the Problem

The first step was to move beyond the abstract idea of "learning from experience" and adopt the formal language of mathematics.

The Markov Decision Process (MDP)

The Logic: Before an agent can learn, its world must be defined. We need a language to describe the environment, the choices the agent can make, and the goals it should pursue. The Markov Decision Process (MDP) provides this language. It assumes that the future is only dependent on the present state, not the past (the Markov Property), which simplifies the problem immensely.

The Math: The MDP is a tuple (S,A,P,R,γ)(S, A, P, R, \gamma)(S,A,P,R,γ), defining:

- SSS: A set of states.

- AAA: A set of actions.

- P(s′∣s,a)P(s'|s, a)P(s′∣s,a): The probability of transitioning to state s′s's′ from state sss after taking action aaa.

- R(s,a,s′)R(s, a, s')R(s,a,s′): The reward received after the transition.

- γ\gammaγ: A discount factor that prioritizes immediate rewards.

The agent's goal is to learn a policy π(a∣s)\pi(a|s)π(a∣s) that maximizes the expected discounted return, J(π)J(\pi)J(π).

J(π)=Eτ∼π[∑t=0Tγtrt]J(\pi) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^T \gamma^t r_t \right]J(π)=Eτ∼π[t=0∑Tγtrt]This objective function is the guiding light for all subsequent algorithms. It defines what "good" behavior is and provides a metric to optimize.

graph TD

A[State: s_t] --> B{Agent};

B -- Action: a_t --> C(Environment);

C -- Reward: r_t --> D[Update];

C -- Next State: s_{t+1} --> A;

Phase 2: The Rise of Policy Gradients

While value-based methods like Q-learning are fundamental, my journey focused on policy-based methods, which optimize the policy's parameters directly.

Learning 1: The Policy Gradient Theorem (REINFORCE)

The Logic: How can we teach an agent to prefer good actions over bad ones? The most direct way is to "reinforce" behaviors that lead to good outcomes. If a sequence of actions results in a high total reward, we should increase the probability of taking those specific actions in those specific states again. This is the core intuition behind policy gradients.

The Math: The Policy Gradient Theorem (Sutton et al., 2000) provides a way to compute the gradient of the expected return with respect to the policy parameters θ\thetaθ. The resulting algorithm, REINFORCE, updates the policy by pushing it in the direction of the gradient.

∇θJ(πθ)=Eτ∼πθ[∑t=0T∇θlogπθ(at∣st) R(τ)]\nabla_\theta J(\pi_\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi_\theta} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^T \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t \mid s_t)\, R(\tau) \right]∇θJ(πθ)=Eτ∼πθ[t=0∑T∇θlogπθ(at∣st)R(τ)]Takeaway: We can directly optimize the policy by increasing the log-probability of actions, scaled by the total reward of the trajectory they belong to. However, this approach is incredibly noisy. Every action in a successful trajectory is reinforced, even the ones that were mistakes. This leads to very high variance and unstable learning.

Learning 2: Variance Reduction with Baselines and Advantage

The Logic: Instead of asking "was the outcome of this trajectory good?", it's more effective to ask "was the outcome of this action better than expected?". If an action leads to a return of 100, but we expected a return of 99, it was only slightly better than average. If we expected a return of -50, it was exceptionally good. This relative measure, the Advantage, is a much cleaner learning signal.

The Math: To achieve this, we introduce a state-dependent baseline, b(st)b(s_t)b(st), which is typically the state-value function Vπ(st)V^\pi(s_t)Vπ(st). The policy gradient is modified to use the Advantage Function, Aπ(st,at)=Qπ(st,at)−Vπ(st)A^\pi(s_t, a_t) = Q^\pi(s_t, a_t) - V^\pi(s_t)Aπ(st,at)=Qπ(st,at)−Vπ(st), which can be estimated with A^t=Rt−V(st)\hat{A}_t = R_t - V(s_t)A^t=Rt−V(st).

Takeaway: Using the advantage function dramatically reduces the variance of the policy gradient without changing its expected value. This is a foundational concept for all modern actor-critic algorithms, which learn both a policy (the actor) and a value function/baseline (the critic).

Learning 3: The Danger of Large Steps (TRPO)

The Logic: In deep learning, we take small steps in the direction of the gradient. But in RL, a seemingly small change in the policy's parameters can lead to a catastrophic drop in performance. How can we take the largest possible step to speed up learning, without risking collapse? The answer is to constrain how much the policy's behavior can change, rather than its parameters.

The Math: Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO) (Schulman et al., 2015) formalizes this. It maximizes a surrogate objective function (which approximates the expected return) subject to a constraint on the average KL-divergence between the old and new policies.

maxθ Es∼πθold[πθ(a∣s)πθold(a∣s) A^θold(s,a)]subject toDˉKL (πθold ∥ πθ)≤δ\max_\theta \; \mathbb{E}_{s \sim \pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}} \left[ \frac{\pi_\theta(a \mid s)}{\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(a \mid s)} \,\hat{A}_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(s,a) \right] \quad \text{subject to} \quad \bar{D}_{\mathrm{KL}}\!\big(\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}} \,\|\, \pi_\theta\big) \le \deltaθmaxEs∼πθold[πθold(a∣s)πθ(a∣s)A^θold(s,a)]subject toDˉKL(πθold∥πθ)≤δTakeaway: Constraining the KL-divergence ensures that the new policy remains in a "trust region" around the old one, leading to stable, monotonic improvements. However, the algorithm is a second-order method and is complex to implement.

Learning 4: Better Advantage Estimation (GAE)

The Logic: The quality of our advantage estimate is critical. A simple one-step TD error is low variance but can be very biased. A full Monte Carlo return is unbiased but has high variance. There must be a way to balance the two.

The Math: Generalized Advantage Estimation (GAE) (Schulman et al., 2015) provides an elegant solution. It computes the advantage as an exponentially-weighted sum of TD errors, controlled by a parameter λ∈[0,1]\lambda \in [0, 1]λ∈[0,1].

A^tGAE(γ,λ)=∑l=0∞(γλ)lδt+lwhereδt+l=rt+l+γV(st+l+1)−V(st+l)\hat{A}^{\text{GAE}(\gamma, \lambda)}_t = \sum_{l=0}^{\infty} (\gamma \lambda)^l \delta_{t+l} \quad \text{where} \quad \delta_{t+l} = r_{t+l} + \gamma V(s_{t+l+1}) - V(s_{t+l})A^tGAE(γ,λ)=l=0∑∞(γλ)lδt+lwhereδt+l=rt+l+γV(st+l+1)−V(st+l)When λ=0\lambda=0λ=0, this is the simple TD error (high bias, low variance). When λ=1\lambda=1λ=1, it is the Monte Carlo estimate (low bias, high variance).

Takeaway: GAE provides a tunable knob to control the bias-variance trade-off in the advantage estimate, which has become a standard component in high-performance policy gradient implementations.

Phase 3: Practical, State-of-the-Art Algorithms

This phase was about implementing and understanding the algorithms that dominate modern RL research.

Learning 5: Simplifying Trust Regions (PPO)

The Logic: TRPO is powerful but computationally expensive. Can we get the same stability benefits with a simpler algorithm that only uses first-order gradients? Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) (Schulman et al., 2017) does exactly this. Instead of a hard constraint, it uses a penalty to discourage the policy from changing too much.

The Math: The key is the clipped surrogate objective. It clips the probability ratio rt(θ)=πθ(at∣st)πθold(at∣st)r_t(\theta) = \frac{\pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)}{\pi_{\theta_{old}}(a_t|s_t)}rt(θ)=πθold(at∣st)πθ(at∣st) to prevent it from moving outside a small interval [1−ϵ,1+ϵ][1-\epsilon, 1+\epsilon][1−ϵ,1+ϵ].

LCLIP(θ)=E^t[min(rt(θ) A^t, clip(rt(θ),1−ϵ,1+ϵ) A^t)]L^{\text{CLIP}}(\theta) = \hat{\mathbb{E}}_t \left[ \min\Big( r_t(\theta)\,\hat{A}_t,\; \mathrm{clip}\big(r_t(\theta), 1-\epsilon, 1+\epsilon\big)\,\hat{A}_t \Big) \right]LCLIP(θ)=E^t[min(rt(θ)A^t,clip(rt(θ),1−ϵ,1+ϵ)A^t)]If the advantage A^t\hat{A}_tA^t is positive, the objective increases with the ratio, but the min function prevents it from getting too large. If the advantage is negative, the objective decreases, but the clipping prevents the update from being excessively large.

graph TD

A[Calculate Ratio: r_t];

B[Calculate Advantage: A_t];

A --> C{Advantage > 0?};

B --> C;

C -- Yes --> D[Encourage action, but clip objective if r_t > 1+ε];

C -- No --> E[Discourage action, but clip objective if r_t < 1-ε];

Takeaway: PPO provides a first-order, easy-to-implement algorithm that captures the stability and reliability of TRPO, making it a default choice for many RL problems.

Learning 6: Off-Policy Continuous Control (DDPG)

The Logic: On-policy methods are sample-inefficient because they throw away old data. For continuous control (like robotics), this is wasteful. Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) (Lillicrap et al., 2015) uses a replay buffer of past experiences to learn "off-policy." It learns a deterministic actor policy (which gives a precise action, not a probability) and a critic that estimates the Q-value of that action.

Takeaway: Off-policy learning with a replay buffer dramatically improves sample efficiency. However, DDPG is notoriously unstable and sensitive to hyperparameters, largely because the critic systematically overestimates Q-values, leading the actor to exploit non-existent advantages.

Learning 7: Stabilizing Actor-Critics (TD3)

The Logic: If DDPG is unstable because it trusts a single, optimistic critic, why not use two critics and trust the more pessimistic one? And if the actor is learning too quickly from a noisy critic signal, why not slow it down? These are the core ideas behind TD3.

The Math & Methods: Twin Delayed DDPG (TD3) (Fujimoto et al., 2018) makes three specific fixes to DDPG:

- Clipped Double Q-Learning: It learns two Q-functions (the "twins") and uses the minimum of the two Q-values in the Bellman target. This helps mitigate overestimation.

- Delayed Policy Updates: The policy and target networks are updated less frequently than the value network, giving the critic time to converge to a better estimate before the actor uses it.

- Target Policy Smoothing: Small amounts of noise are added to the target action during critic updates. This creates a smoother Q-value landscape and makes the policy more robust.

The practical impact is profound. The videos below show a cheetah agent's progress, illustrating the difference between an unstable early algorithm and a robust, well-trained policy. Early algo

Trained policy

Takeaway: The stability of modern actor-critic algorithms comes from carefully identifying and addressing specific sources of error, such as overestimation bias in the critic.

Phase 4: From Algorithms to a Generalizable Drone Racing System

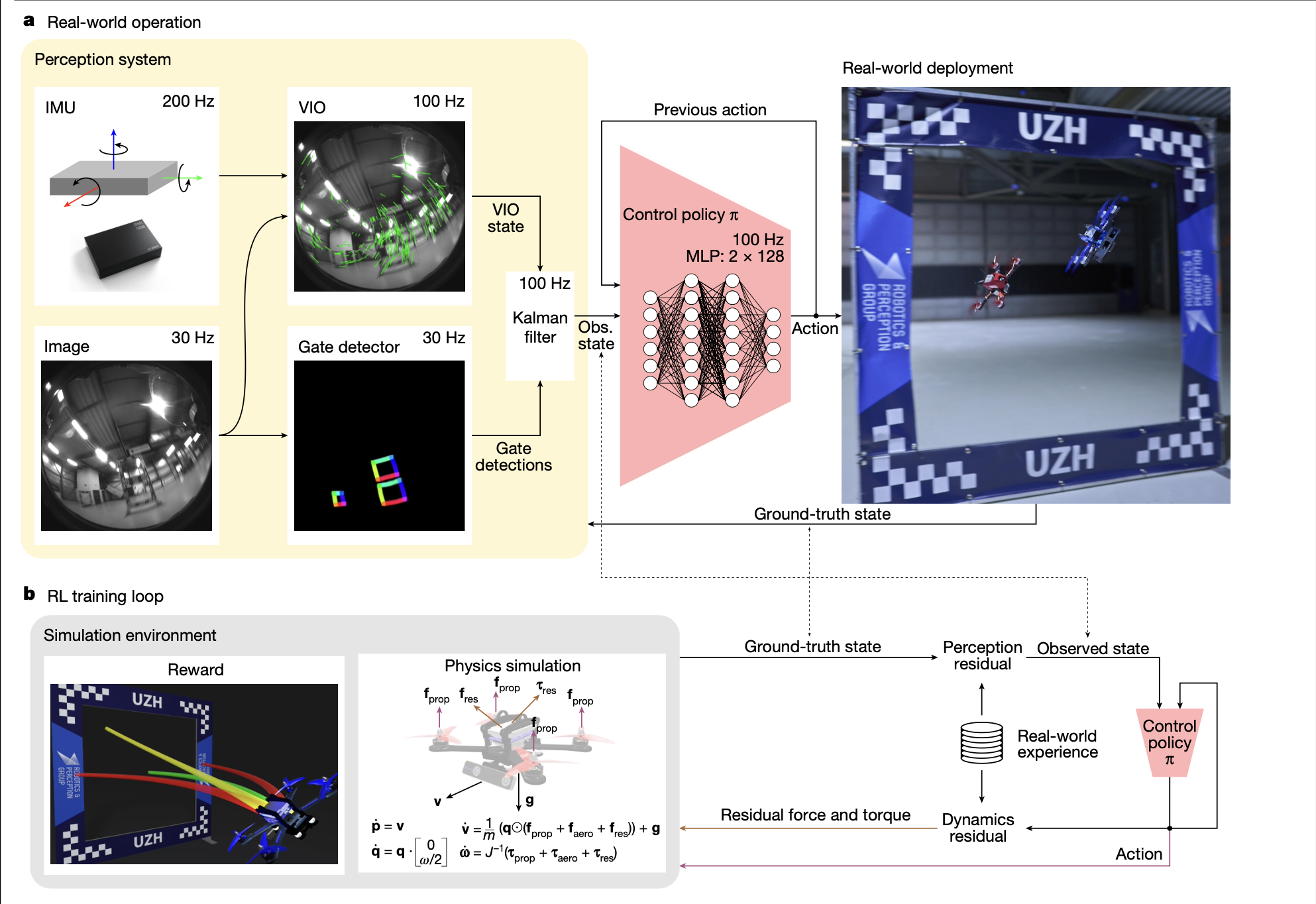

A real-world embodiment of these ideas is Swift, the champion-level drone racing system developed at the Robotics and Perception Group, University of Zurich (Kaufmann et al., 2024). Trained end-to-end with PPO in simulation and then transferred to real FPV tracks, Swift pairs a carefully engineered perception and state-estimation stack with a lightweight neural policy that can reliably beat human world champions.

Swift system developed at Robotics and Perception Group, University of Zurich

Swift sits within a broader ecosystem of work on agile flight and autonomous racing—comparing optimal control to RL, leveraging differentiable physics for vision-based flight, and learning quadrotor control directly from visual features (Brunnbauer et al., 2021; Gehrig et al., 2021; Kaufmann et al., 2019). Together, these systems make it clear that success is not just about choosing the right RL algorithm, but about composing perception, dynamics, and control into a coherent architecture.

My current direction builds directly on this line of work: Transformer-augmented reinforcement learning for drone racing. Here, all the ideas from Phases 1–3—policy gradients, advantage estimation, trust-region style updates (PPO), and stability techniques from TD3—are no longer abstract tools, but design constraints for a full end-to-end system.

Rather than treating RL as a monolithic "black box," the system is deliberately modular. A Transformer-based vision encoder learns a latent representation of the track and gate geometry, while a Transformer PPO policy consumes this representation together with state estimates to output low-level thrust and body-rate commands at real-time frequencies. The classic questions of RL (how to define the return, how large an update to take, how to manage partial observability) now show up as concrete engineering choices about reward shaping, temporal context length, and the structure of the perception–control interface.

The challenges are therefore both algorithmic and systemic:

- Reward Shaping for Racing: The reward must balance raw lap time with stability, gate alignment, and control smoothness, while avoiding degenerate shortcuts that "game" the track.

- Generalization and Sim-to-Real: Policies are trained with heavy domain randomization and residual modeling so that a controller learned in simulation can transfer to new tracks and real hardware without catastrophic failure.

- Latency and Integration: Every component—vision backbone, policy network, and sensor fusion stack—must fit within a tight real-time budget on embedded compute, forcing architectural decisions that respect both theory and hardware.

Phase 4 is thus less about inventing a new algorithm and more about composing everything learned so far into a coherent, deployable system—one that can race competitively, generalize beyond a single environment, and serve as a template for future embodied RL projects.

graph TD

Sim[Simulated Drone Racing Tracks] --> Vision[Transformer Vision Encoder];

Vision --> Policy[Transformer PPO Policy];

Policy --> Drone[Real Quadrotor];

Drone -- Telemetry & Video --> Data[Real-World Data];

Data -- Residual Modeling & Fine-Tuning --> Sim;

Core Papers

- DDPG: Lillicrap, T. P., et al. (2015). Continuous Control with Deep Reinforcement Learning. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR).

- GAE: Schulman, J., Moritz, P., Levine, S., Jordan, M. I., & Abbeel, P. (2015). High-Dimensional Continuous Control Using Generalized Advantage Estimation. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR).

- Policy Gradients: Sutton, R. S., McAllester, D. A., Singh, S. P., & Mansour, Y. (2000). Policy Gradient Methods for Reinforcement Learning with Function Approximation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 13.

- PPO: Schulman, J., Wolski, F., Dhariwal, P., Radford, A., & Klimov, O. (2017). Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms. arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.06347.

- TD3: Fujimoto, S., van Hoof, H., & Meger, D. (2018). Addressing Function Approximation Error in Actor-Critic Methods. International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML).

- TRPO: Schulman, J., Levine, S., Abbeel, P., Jordan, M., & Moritz, P. (2015). Trust Region Policy Optimization. International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML).

Additional Influential Papers & Resources

- Duan, Y., Chen, X., Houthooft, R., Schulman, J., & Abbeel, P. (2016). Benchmarking Deep Reinforcement Learning for Continuous Control. International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML).

- Kaufmann, E., et al. (2024). Champion-Level Drone Racing Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. Nature.

- OpenAI. (n.d.). Spinning Up in Deep RL. Retrieved from https://spinningup.openai.com/

- Sutton, R. S., & Barto, A. G. (2018). Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction. MIT Press.

- Zhou, Y., et al. (2024). Genesis: A General-purpose, Language-driven, Embodied AI System. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.11904.

Phase 4 papers

- Brunnbauer, A., et al. (2021). Reaching the Limit in Autonomous Racing: Optimal Control versus Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters (RA-L).

- Gehrig, M., et al. (2021). Back to Newton’s Laws: Learning Vision-based Agile Flight via Differentiable Physics. Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL).

- Lu, C., et al. (2022). Transformers in Reinforcement Learning: A Survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.13436.

- Laskin, M., et al. (2020). Stabilizing Deep Q-Learning with ConvNets and Vision Transformers under Data Augmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.00067.

- Kaufmann, E., et al. (2019). Learning Quadrotor Control from Visual Features Using Differentiable Simulation. Robotics: Science and Systems (RSS).